Software

I currently (as of Spring 2019) work at an advertising agency specializing in 3D product customization. I developed (and currently maintain) their web-based 3D rendering platform using WebGL, with an emphasis on photorealism. By strictly focusing on product visualization, I was able to create a rendering library and supporting framework much lighter and more performant than existing engines, including Three.js, Babylon.js, and PlayCanvas.

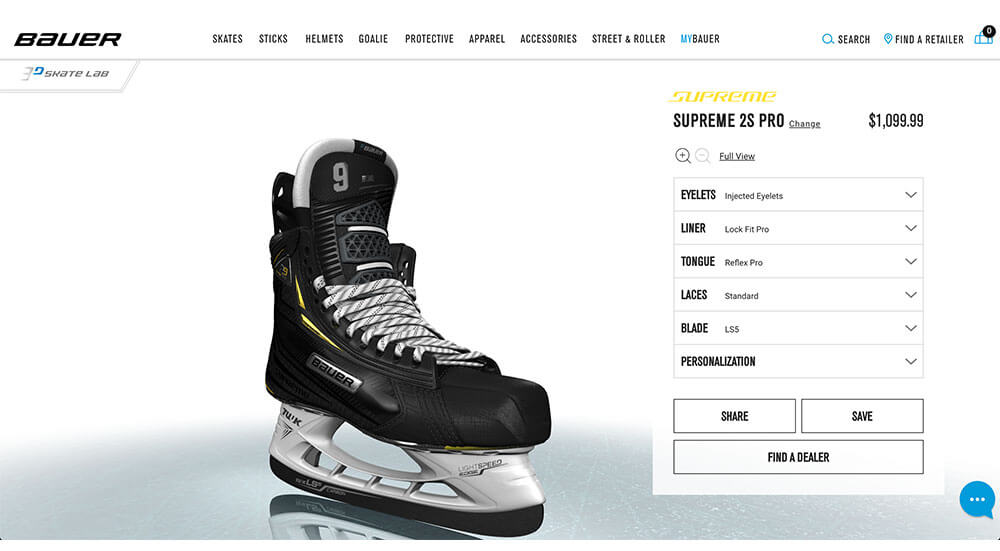

The framework supports a standardized, physically-based metalness/roughness workflow, with specialized support for iridescence, instancing, advanced text effects, soft shadows, reflections, and custom, per-client shader extension capabilities. Visual fidelity is consistent across a range of platforms, including desktop, tablet, and mobile.

Front-end developers typically construct a user-interface around the 3D canvas that connects to the rendering framework to customize the visual appearance of the 3D scene at run-time (e.g. editing text, changing colors/materials, uploading images). A back-end renderer (running in the cloud on a high-powered NVIDIA Tesla card) is able to generate static images and short videos from the 3D content, for e.g. shopping carts and social media.

Clients utilizing our 3D capabilities include Levi's, Under Armour, Timex, Bauer, Giro, Carhartt and Benchmade. To see the 3D in action, try out the interactive experience!

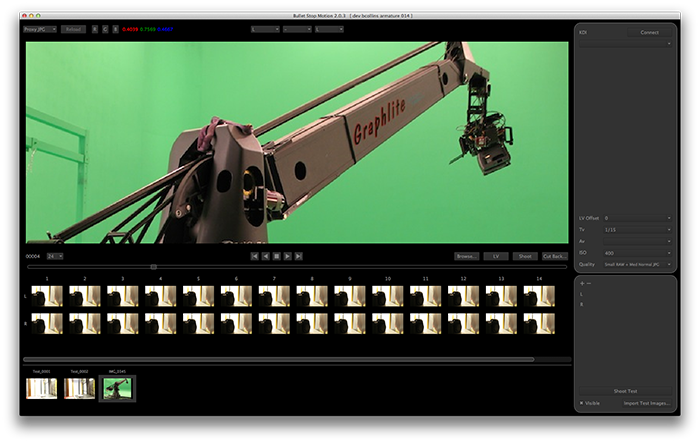

Previously, I worked as a software engineer at Laika Entertainment, a film studio in Portland, Oregon specializing in stop-motion animation. I developed an in-house software application designed for motion control and lighting engineers, to aid in generating sophisticated on-set camera moves.

The software, called Bullet Stop Motion, was written in modern C++ and made heavy use of OpenGL to provide live video feeds from a high-end Canon camera while rendering a variety of compositing tools onto an overlay layer. It was also capable of loading 3D assets and compositing them directly over green screens, giving directors a window into the virtual worlds of their films.

The software was designed from the outset to work well with the KDI interface hardware and shoot switch I designed (see hardware section below). Having all of these tools in-house meant that I could deliver custom solutions to production challenges in a matter of days. Even the best, highest caliber commercial packages couldn't match this level of flexibility and service.

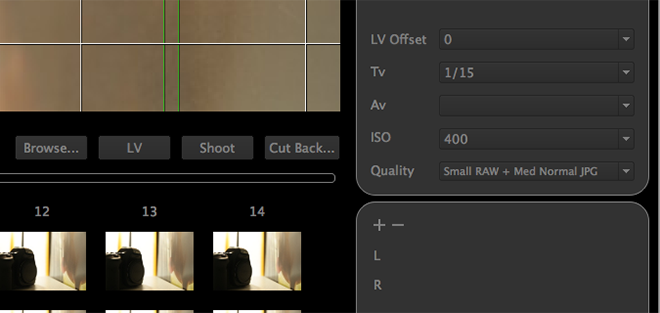

A close-up of the camera control interface is shown above. Bullet could completely control most pro-sumer grade Canon cameras, like the 5D Mark III, with controls for shutter speed, aperture, ISO, raw size, and live view offset. High resolution frame-by-frame playback was supported, with selectable framerates from 2 to 48 fps. High speed playback was accomplished by filling OpenGL pixel buffers with image data from the camera using an MMX/SSD SIMD accelerated jpeg library.

The following videos demo various graphics algorithms I have implemented in the past (some quite old now!), including light space perspective shadow mapping, deformable terrain, and dynamic environment mapped reflections. For best effect please watch them at the highest video quality by clicking the gear icon after playback starts.

Hardware

While hardware motion control systems have changed little over the past two decades, stop motion application software has forged ahead, taking advantage of the latest features from DSLR cameras and PC graphics hardware. In late 2010, I designed and constructed an interface device called the KDI that allows these two different systems to communicate, giving stop motion animators and motion control engineers unprecented control over their shots.

Virtually every frame from Laika's 2012 3D film Paranorman was captured using a KDI device. The entire project, from the first hand-soldered prototypes to the final production units, took about 6 months, including front/rear panel design, PCB design, and firmware development. After building the first few production units myself, I worked with an engineering technician to have a total of 60 units made for the stage floor. The hardware has remained stable for over two years, but the firmware continues to be improved to work with new cameras and to cater to additional photographic techniques (e.g. motion-blur, front-light/back-light).

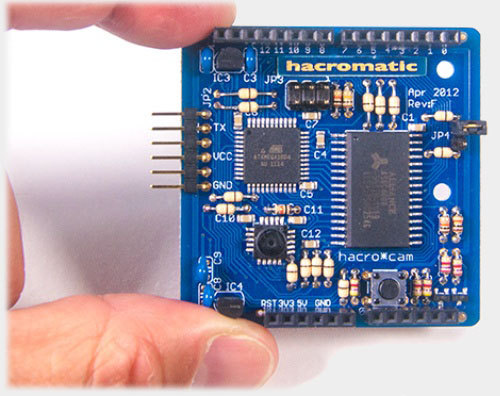

The KDI is powered by an 8-bit Atmel AVR chip that communicates over USB to the PC and over a galvanically isolated serial line to the motion control system. It has evolved into roughly 4000 lines of optimized C++ code that manages multiple motion control systems, advanced camera triggering, a variety of stop motion software packages, and exposes all of the extended functionality of my custom shoot switch, described next.

During principal photography, stop motion animators use a "shoot switch", a simple two-button handheld device that triggers the capture of a frame of animation and advances the motion control system to the next frame. The KDI is designed to be triggered by this type of switch, but it only triggers a single frame for each button press. I designed and built an improved switch that allows the animator to shoot multiple frames on a single button press. The animator is then free to work on something else until the shoot switch display indicates that shooting is complete.

In late 2011 my tinkering with the TCM8230MD camera chip from Toshiba led to the creation of an open source hardware company called Hacromatic. The company's main product, a kit called the HacroCam, was an embedded camera board in an Arduino shield footprint, specifically designed to allow people to do interesting things with pixels immediately after image capture. Rather than just pumping out jpegs, you got full access to the uncompressed RGB image, and with 16K of program flash you could do lots of interesting hacks, including software jpeg, motion detection, edge detection, and color blob tracking (in addition to just taking regular photos).

To make all of this work on an 8-bit micro proved to be an interesting challenge. With only 8 instruction cycles per pixel, I had to program the capture routine in assembly to keep up with the camera. All of the source code for the firmware should still be available at the Wayback Machine link above. A clever hacker from Italy managed to fit a complete software jpeg implementation into the firmware, and a group at Purdue University used the camera as part of a machine vision system for their coffee roaster.

Papers

|

|

Film Credits

Book Credits (as technical reviewer)

The above projects were chosen to be representative of the kind of work I've been doing the past few years. From circuit board layout and enclosure design, to 3D crowd rendering and vehicle simulation, the projects I've been fortunate enough to be involved with have given me a unique ability to plan, design, and execute under rigorous time and cost constraints.

I am equally comfortable working on large-scale cross-platform software systems or tightly-constrained microcontroller assembly code. I have implemented algorithms from SIGGRAPH papers, and authored and presented my own papers. I served as technical editor for Addison Wesley's OpenGL books for many years. While highly fluent in C++, Python, and AVR assembly, I am comfortable in a variety of additional languages.